When he is not hauling concrete blocks on a construction site in northern Iraq, Jamal Hussein devotes his time to preserving the gentle art of Arabic calligraphy.

Though he has won awards in numerous competitions, Hussein acknowledged that “you can’t live on this”, the artistic handwriting of Arabic script.

“I have a big family. I have to find other work,” said the father of 11, who is 50 years old and earns his keep working on building sites in the Iraqi Kurdish town of Ranya.

Last week, the United Nations culture agency declared Arabic calligraphy an “Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity”, following a campaign by 16 countries led by Saudi Arabia and including Iraq.

“The fluidity of Arabic script offers infinite possibilities, even within a single word, as letters can be stretched and transformed in numerous ways to create different motifs,” UNESCO said on its website.

Abdelmajid Mahboub from the Saudi Heritage Preservation Society involved in the proposal to UNESCO said the number of specialised Arab calligraphic artists had dropped sharply.

Hussein is one of them, and he welcomed the UNESCO decision.

He hopes it will push “the Iraqi government and the autonomous Kurdistan region to adopt serious measures” to support calligraphy — “khat” in Arabic — and its artists.

Practising since the 1980s, his decades of experience and participation in competitions are attested to by about 40 medals and certificates displayed at his home.

No support

In October he came second in an Egyptian online competition, and is now training for a contest next month in the Iraqi holy Shiite city of Najaf.

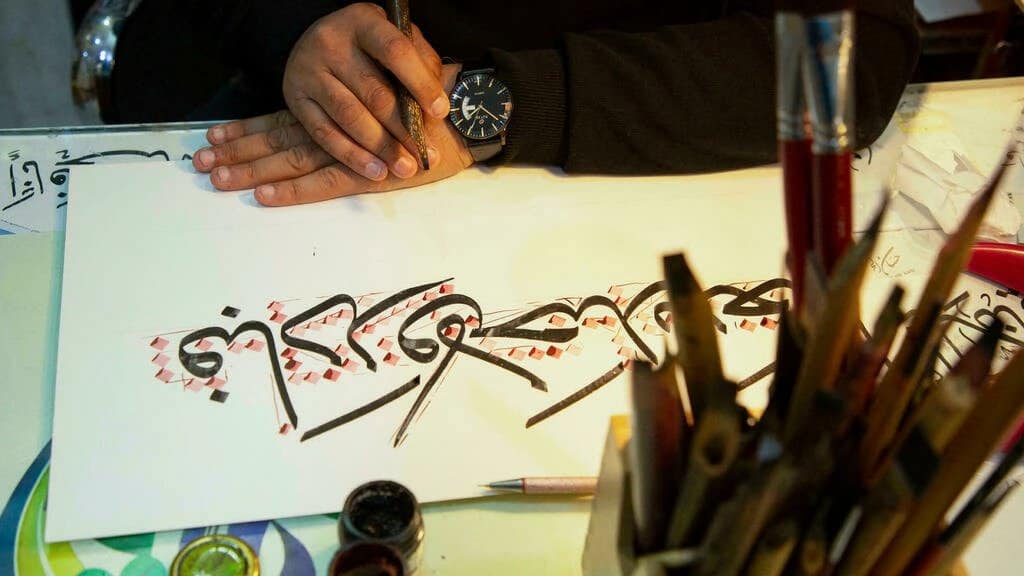

Hussein’s creations are made with a reed pen that he buys from Turkey or Iran. He sometimes sells the work for posters, shop displays and even tombstones, he said.

For decades, in the major regional centres of Cairo, Amman, Beirut or Casablanca, calligraphy was displayed on storefronts, on walls featuring popular sayings, or on plaques at the entrances of buildings to signal the presence of a lawyer or a doctor.

Today, the remnants of this calligraphy are only visible on the faded facades of old shops.

Still, nostalgia for the vintage aesthetic has become something of a trend, as hipsters of the region post pictures of their discoveries for their followers on social media.

But in impoverished, war-scarred Iraq, there is no support from the government “whether for calligraphy or for other arts,” Hussein lamented.

“Because of technology, the sanctity of calligraphy has declined,” he said.

“Calligraphy requires more time, more effort and is more costly. People are moving towards cheaper technological production.”

But it is impossible for Hussein to abandon his art. He dreams of “travelling to Egypt or Turkey and living there temporarily to improve my khat”.

At the other end of Iraq, in the southern city of Basra, Wael al-Ramadan opens his shop in an alley.

A client arrives to inquire about the preparation of an administrative stamp used to confirm attendance.

Ramadan seizes one of his sharp-nibbed pens and starts again to practise the art which his father introduced him to when he was still a child.

On paper he slowly begins to trace the requested words, with Arabic letters distinguished by their elegant curves.

Like his fellow calligrapher Hussein, Ramadan applauds UNESCO for its “great support for calligraphy and calligraphers all over the world.”

Ramadan earns money by teaching the discipline in schools but also sells his skill for advertisement purposes.

“We hope that the government will take an interest in this art, through exhibitions and competitions,” said Ramadan, 49, who is clad in black with a shaven head.

“The survival of Arabic calligraphy depends on the support of the state.”

It depends, too, on the devotion of men like Hussein and Ramadan.

“I obviously hope that my children will succeed me, just like I followed in my father’s footsteps,” Ramadan said with a smile.