Nobel laureate Abdulrazak Gurnah has pledged to keep speaking out on migration and other hotly-contested issues, branding Brexit “a mistake” and European governments’ policies “inhumane”.

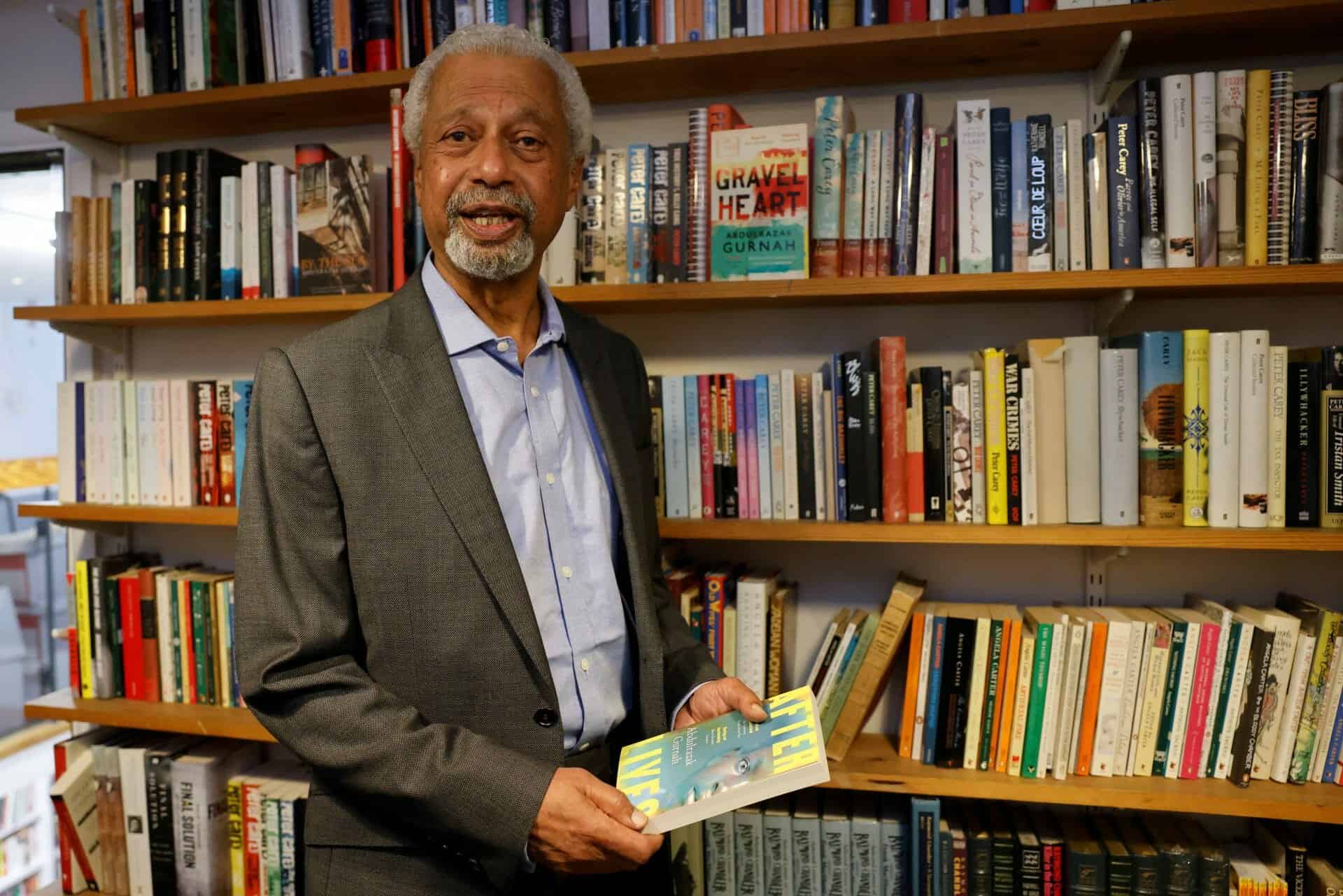

The 72-year-old novelist, whose decades-spanning body of work is rooted in colonialism and immigration, landed literature’s top award Thursday for his unflinching portrayal of their effects on the refugee experience.

“I write about these conditions because I want to write about human interactions and… what is it that people go through when they are reconstructing lives,” he told reporters at a news conference in London.

“I didn’t know it was going to happen,” he said of scooping the accolade. “You write the best you can, and you hope it will succeed and do well.”

But the acclaimed author of 10 novels and several short stories was at pains to point out he would keep speaking candidly on the issues that have shaped his work and worldview.

“I’m speaking because this is how I would speak… whether I had won the Nobel prize or not. I’m not playing a role, I’m saying what I think.”

‘I’m from Zanzibar’

Gurnah, the fifth African-born writer to win the literature Nobel, fled to Britain from Zanzibar in late 1967, later acquiring British citizenship.

Growing up speaking Swahili, he had also learned English on the Indian Ocean archipelago, which was a British protectorate until unification with Tanzania.

Despite going on to write his literature in English, Gurnah retains links with, and an identity shaped by, his homeland that has informed his novels.

“I’m from Zanzibar, there’s no confusion in my mind about that,” he explained.

“My experience of both work as well as living has been here in Britain. But that is not entirely what constitutes your imaginary life or imaginative life.

“So I don’t feel the question of where do you come from is one that answers the question of what your work does.”

Self-deluding

After more than five decades in the UK, Gurnah argued there is now less blatant racism and greater awareness of the issue, but that the country’s institutions remain “just as mean and just as authoritarian as they were”.

He cited the “Windrush” scandal, which saw immigrants from the Caribbean targeted by the government in recent years despite moving to Britain legally in the 1950s and 1960s, and the hostile treatment of asylum-seekers.

“This seems to me to be just a continuation of the same ugliness,” the writer noted.

Meanwhile, Gurnah said he was “suspicious of the force” behind Britain’s withdrawal from the European Union last year, which proponents campaigned for in 2016 partly on the basis of limiting immigration and recapturing “lost freedoms”.

“Maybe there is something nostalgic in that but there is also perhaps something self-deluding about that,” he added.

“Quite simply, I think it’s a mistake.”

Lack of compassion

The Nobel winner was also unsparing in his criticisms of other European countries’ politics, such as Germany, which he argued has not “faced up to its colonial history”.

His latest book, “Afterlives”, chronicles a little boy stolen from his parents by German colonial troops who later returns to his village to find his parents gone and his sister given away.

Gurnah said current European governments’ hardline reaction to increases in immigration from Africa and the Middle East was both heartless and illogical.

“In this terrified response — ‘who are these people who are coming?’ — (there) is a lack of humanity, a lack of compassion.

“Also, there is not only no moral but no rational grounds: these people are not coming with nothing, they’re coming with youth, energy, potential.

“To simply focus on the idea that ‘here they are, they’re coming to snatch something from our prosperity’ is inhumane.”