DAVOS — Corruption is an enduring and disturbing thread in the complex web of international events. It affects all levels of society, regardless of culture, economic system, or location, and can range from underhanded dealings in back alleys to elaborate financial schemes in the halls of power. Fighting corruption is a defining issue for governments and organizations worldwide as we navigate the complicated landscape of the 21st century.

Corrupt practices have far-reaching consequences that damage society, weaken faith in institutions, slow economic growth, and destroy the social fabric. Unfaltering focus, fresh approaches, and worldwide cooperation are required to solve this complex problem.

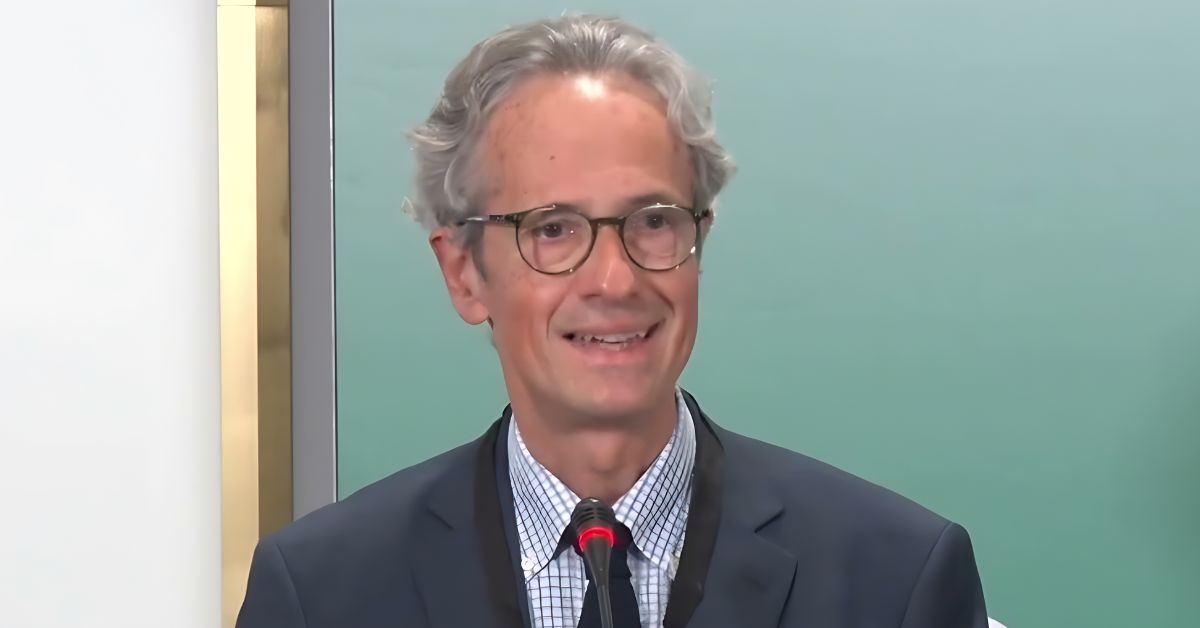

In an exclusive Q&A interview with Francois Valerian, the Chairman of Transparency International, during the World Economic Forum 2024 in Davos, TRENDS delves into the intricate web of global corruption, financial opacity, and the challenges institutions worldwide face. As we embark on the journey of 2024, Valerian shares insights into the persisting challenges and evolving landscape of corruption that spans nations, economies, and sectors.

Excerpt:

Q: What’s your outlook for 2024 in terms of corruption?

A: Our main challenge is to fight the global economy of corruption that comes from bribes in all countries, including those with a massive inflow of money, like Switzerland, France, Germany, the UK, and the US.

Q: Do you think that corruption in corporate or politics has decreased or increased in the past two decades?

A: Unfortunately, it has not decreased globally. We have the laws and the institutions in place, but we need more enforcement and judicial enforcement in most countries; the judiciary system needs more staff, sufficient funding, and, in many cases, more independence from executive power.

Q: What parts of the world are primarily corrupt?

A: I don’t think there are more severe parts than others because all countries contribute to this global corruption economy. Money is stolen in many countries and reinvested in others with active or passive participation in the financial system. So, it’s a global economy. And all countries play their role as they fight and combat corruption.

Q: What should governments do, and what are they lacking? Is more political will needed?

A: Governments must ensure the judiciary system has the means and independence to enforce anti-corruption laws, bring the corrupt to justice, and sentence the guilty effectively.

Q: How do you see that in some cases, a corrupt CEO of a company, even if found guilty, gets away with a fine, while a minor employee goes to jail for $100?

A: It’s problematic when there’s a discrepancy between fines levied on companies or CEOs, who can afford the penalties, and the severity of their offenses. Clearly, we need more deterrent sanctions, including jail time, to address this issue.

Governments must ensure the judiciary system has the means and independence to enforce anti-corruption laws, bring the corrupt to justice, and sentence the guilty effectively.

Francois Valerian, Chairman of Transparency International

Q: Can you cite any examples of good practices that large companies worldwide have adopted?

A: Several companies are making serious efforts to prevent corruption. The challenge is ensuring CEO involvement and ethical behavior. Instead of a good example, I’ll mention Wirecard, a German company that filed for bankruptcy a year ago due to falsified accounts and unethical management, leading to the CEO’s arrest.

Q: What is the size of the global corruption economy?

A: Measuring global corruption is difficult. Our estimates suggest that $1 trillion flows annually from one country to another due to corruption. What needs to accelerate is the implementation of sanctions for incomplete or missing information. Currently, these sanctions aren’t deterrent enough. The next step is ensuring public access to registries and imposing stringent sanctions for non-compliance.

Q: How credible is the fight against corruption? For example, the US requests Switzerland to enhance its financial transparency, while the state of Delaware shows similar opacity.

A: Recent US laws have called for beneficial ownership transparency and have been adopted, with the most crucial law taking effect on January 1. Its implementation is now crucial, yet there is ongoing debate in Congress about delaying this process. We need direct action across all US states.

Q: Between organized crime and political corruption, which poses the greater challenge?

A: These challenges are interconnected. In many countries, organized crime has successfully infiltrated the state apparatus, turning it into an instrument against the populace. This significant issue was a focus of our advocacy at last December’s conference of the state parties to the UN Convention against Corruption.

Q: Is technology a help or a hindrance in your efforts?

A: It serves as both. Technology acts as a transparency tool, from smartphone apps that enable reporting of corruption to big data and AI, which reveal corruption patterns. However, it can also aid the corrupt, as seen with cryptocurrency markets facilitating opaque transactions from rubles in Moscow to pounds in London.