The long-frozen Western Sahara conflict pitting Morocco against the Polisario Front independence movement has flared in recent months, worsening already tense relations between the kingdom and its Polisario-backing neighbor, Algeria.

The killing of three Algerians on a highway through the territory, in what Algiers says was a Moroccan strike, has raised fears of escalation.

So, what is at stake, and what are the risks?

How do things stand?

A former Spanish colony with extensive phosphate reserves and rich Atlantic fishing grounds, the Western Sahara is seen by Morocco as its own sovereign territory.

To stake Morocco’s claim, the current king’s father, Hassan II, sent 350,000 civilian volunteers on the iconic Green March into the territory in 1975 — 46 years ago this Saturday.

Shortly afterwards, Spain withdrew, leaving Morocco and fellow claimant Mauritania to fight it out with the Polisario Front, which proclaimed a Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic, with support from Algeria, a state with strong anti-colonial roots.

A 15-year war ensued during which Mauritania sued for peace but Morocco gradually overran 80 percent of the territory before a UN-monitored ceasefire took effect in 1991.

The ceasefire deal envisaged a UN-supervised self-determination referendum for the territory with all options on the table but Morocco has since rejected any vote that includes independence as an option, offering only limited autonomy instead.

How did things heat up again?

In December last year, Morocco normalized diplomatic relations with Israel and as a quid pro quo, the US administration of Donald Trump recognized the kingdom’s sovereignty over Western Sahara.

That came just weeks after the Polisario declared the 1991 ceasefire null and void, after Moroccan forces entered no man’s land to break a blockade by Sahrawi activists of a highway linking Moroccan-controlled territory with Mauritania.

The Polisario says that both the highway and the military incursion violated the decades-old truce.

“We are facing a pattern of escalation,” said Dalia Ghanem, a resident scholar and Algeria specialist at the Carnegie Middle East Center.

The Polisario has since launched multiple attacks on Moroccan forces, killing six Moroccan soldiers, according to a Moroccan source.

The kingdom’s alleged use of Israeli spyware against Algerian officials and a Moroccan official’s expression of support for separatists in the mainly Berber Kabylie region east of Algiers prompted Algeria to break off ties completely in August.

The succession of events has pushed Algeria to take “an increasingly aggressive stance towards its neighbour,” said Riccardo Fabiani, North Africa project director at the International Crisis Group.

Then, this week, the Algerian presidency reported that “three Algerians were assassinated… in a barbaric strike on their trucks” in an area of the Western Sahara under Polisario control, an attack for which it blamed Morocco.

“Even if it’s possible that Morocco believed that they were Polisario forces, they killed civilians,” said Youssef Cherif, director of Columbia Global Centers in Tunis.

“That shows that they’re more sure of themselves and that they see their sovereignty over the Western Sahara as a fait accompli.”

Cherif said Rabat now wants to impose a new status quo, including by closing a desert highway used by Algerian truckers to shorten the journey between Mauritania and Algeria.

Fabiani said that following Washington’s recognition of its sovereignty, “Morocco has shown a more hardnosed approach to Western Sahara and in its relations with its neighbors, including Spain.”

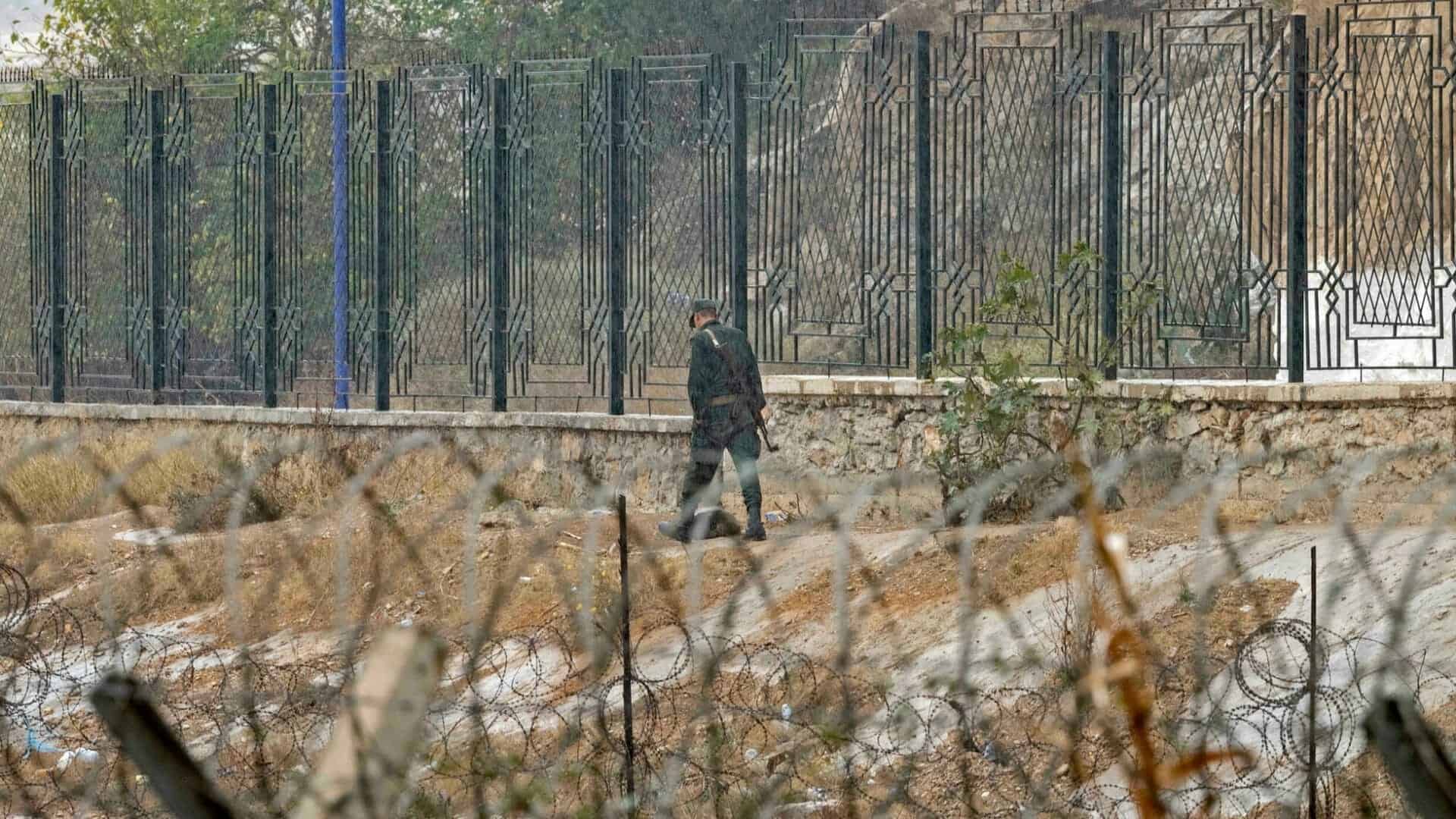

In May, thousands of migrants crossed into the Spanish enclave of Ceuta from Moroccan territory. Many observers believe that the Moroccan authorities let them pass in order to punish Madrid for allowing Polisario chief Brahim Ghali to receive medical treatment in Spain.

What now?

Fabiani says the Western Sahara conflict had long been frozen, discouraging outside actors from getting involved.

“This balance has been modified by the recent developments related to Western Sahara and Israel’s transfer of military equipment to Morocco,” he said.

The new imbalance “is slowly pushing the two countries towards a possible confrontation”, he said.

The Algerian presidency said Monday’s killings would “not go unpunished”.

Ghanem said Algiers “feels compelled to respond”.

“Not doing anything would send the following message: ‘You can attack us, and we will not react’.

“That is not an option, especially with a leadership that has been good at playing on the nationalistic sentiment.”

But Cherif said the two sides were unlikely to risk a direct conflict.

Another Maghreb specialist, who asked not to be identified, said Algeria could move to create “blockages at every level” in international bodies.

That does not bode well for efforts by incoming UN Western Sahara envoy Staffan de Mistura to revive long-frozen talks on a lasting solution for the conflict.