- Saudi clerics say the practice has proliferated since 1996, when the then grand mufti legitimized it with an Islamic edict

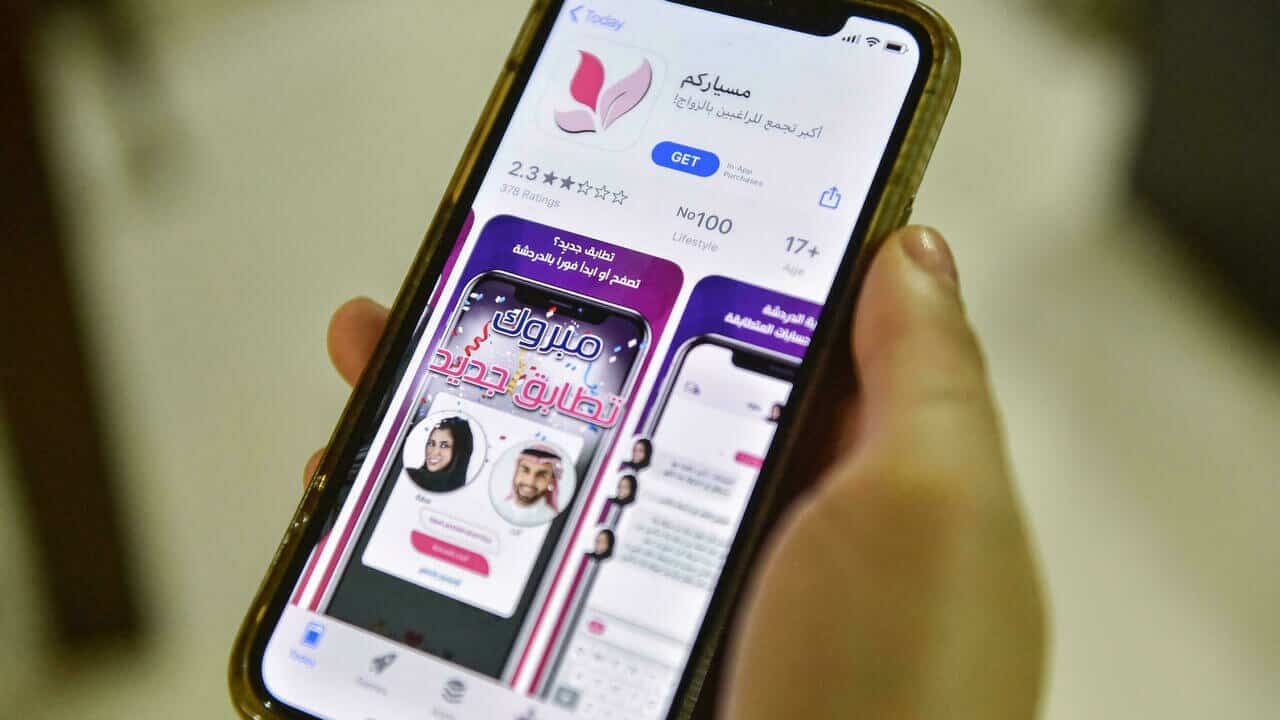

- Saudis, as well as the kingdom’s expat workers, can be seen hunting on dating apps and matrimonial websites for such partners

The Muslim no-strings-attached “misyar” marriage often done in secret is fast pervading Saudi society — a boon for cash-strapped men unable to afford expensive traditional weddings, but deplored by critics for legitimizing promiscuity.

The practice, usually a temporary alliance in which the wife waives some conventional marriage rights such as cohabitation and financial support, has been legally permitted in the conservative Muslim kingdom for decades.

More than a dozen interviews with matchmakers and misyar couples -– including grooms juggling other conventional marriages — offer a window into a phenomenon still shrouded in secrecy and shame, despite its proliferation.

The testimonies highlight how misyar is seen as a hybrid between marriage and singlehood, benefiting polygamists without the stress of maintaining a second household.

Despite its potential for abuse, it also appeals to some women keen to shun patriarchal expectations of traditional marriages, as well as unmarried couples seeking religious cover for sexual relationships, forbidden by Islam outside wedlock.

“Misyar offers comfort, freedom and companionship that is halal (permitted in Islam),” said a Saudi government employee in his 40s, who has been in such a relationship with a Saudi widow in her 30s for more than two years.

He told AFP he had three children from a separate, conventional marriage, and visits his misyar wife in her Riyadh home “whenever” he wants. He did not say what she gained from the secret alliance.

“My (Saudi) friend has had 11 secret misyar wives. He divorces and marries another, divorces and marries another…,” he added, trailing off.

‘No dowry’

Saudis, as well as the kingdom’s expat workers, can be seen hunting on dating apps and matrimonial websites for such partners.

“Misyar is cheaper. There is no dowry, no obligation,” a 40-year-old Egyptian pharmacist in Riyadh told AFP.

He began searching after sending his wife and five-year-old son back to Cairo at the start of the coronavirus pandemic last year, mainly due to rising living costs and an expat levy introduced by Saudi Arabia in recent years.

“Being away from my wife is hard,” he said, adding he had been searching for misyar through “khatba” matchmakers on Instagram who charge as much as 5,000 riyals ($1,333).

“I gave them my preference: weight, size, skin colour… but no match so far.”

Such marriages are often short-lived, with most ending in divorce from anywhere between 14 and 60 days, the kingdom’s Al-Watan newspaper reported in 2018, citing justice ministry sources.

It is touted by some women as a fleeting escape from spinsterhood or a chance for a fresh beginning for divorcees and widows, who otherwise struggle to remarry.

A close associate of a divorced Syrian woman in Riyadh told AFP she was in a secret misyar relationship because she feared her ex-husband, a Saudi, would legally seek custody of her two children if he discovered that she had remarried.

It is impossible to estimate the number of such marriages, many of which are undocumented.

Saudi clerics say the practice has proliferated since 1996, when the then grand mufti, the kingdom’s highest religious authority, legitimized it with an Islamic edict.

But many question the validity of a furtive practice at odds with the main tenets of Islamic marriage, which requires a public declaration.

A prominent Riyadh cleric attributed its proliferation to men unwilling to shoulder the full responsibilities of polygamous marriage, which is permitted in Islam as long as all wives are treated equally.

In a 2019 column in the Saudi Gazette daily, columnist Tariq Al-Maeena described misyar as a “license to have multiple partners without much responsibility or expense”.

“Reports in the Saudi press have spoken of growing concerns over the number of children fathered by Saudi males in their trips abroad, and abandoned for all practical purposes,” he wrote.

Some women are forced to pursue court cases against Saudi men refusing to accept children born into misyar relationships.

“A woman contacted me and said: ‘I am a misyar wife and my husband does not recognise my child’,” the Riyadh cleric told AFP.

“He says ‘the child is not my problem’. I advised her to take him to court and fight for her rights.”