Syria is home to some of the Arab world’s literary giants, and Damascus boasted an abundance of busy bookshops and publishing houses printing and distributing original and translated works.

But the city’s literary flare has faded.

A decade-old civil war, a chronic economic crisis and a creative brain drain that has deprived Syria of some of its best writers and many of their readers, have compounded worldwide problems facing the industry, such as the growing popularity of e-books.

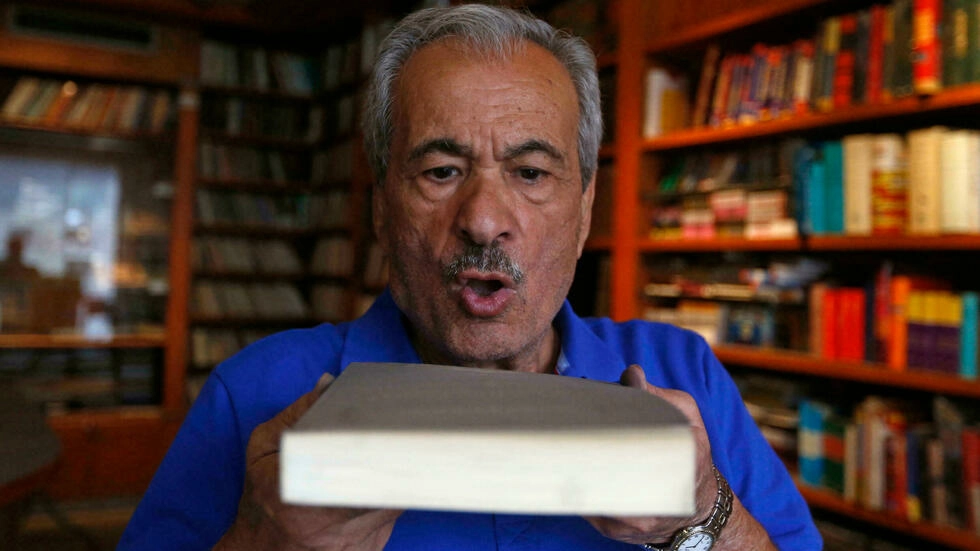

“People can’t afford to read and bookstores can’t cover the expenses of staying open,” said Muhammad Salem al-Nouri, 71, who inherited one of the capital’s oldest bookshops from his father.

Last month, the iconic Nobel bookshop in Damascus, founded in 1970, closed its doors.

The Al-Yaqza bookshop, founded in 1939, shut seven years ago, with a shoe store now taking its place.

A money exchange office has replaced the Maysalun bookshop which was open for four decades.

The Al-Nouri bookstore, founded in 1930, is at risk of meeting the same fate.

“We wanted it to remain for our children and grandchildren,” Nouri told AFP. “But the Al-Nouri bookshop is threatened with closure, as are other bookstores.”

‘Luxury’

The Nouri family currently runs two bookshops in central Damascus.

Three years ago, the family was forced to close a third bookshop they had opened in the capital in 2000 because of poor sales and growing costs.

Its stock remains in place, gathering dust on fully stacked shelves.

On a wooden desk, old photos of celebrity customers, including politicians, artists and poets, are placed on display.

For Sami Hamdan, 40, the cultural heyday of the 1950s and 1960s is long gone.

“The war has destroyed what was left” of a cultural scene that was already in retreat, said the former owner of the Al-Yaqza bookstore.

With 90 percent of the population living below the poverty line and prices skyrocketing in the face of the plummeting value of the Syrian pound, “no one is going to invest in a bookshop during conflict,” Hamdan told AFP.

For Khalil Haddad of the Dar Oussama publishing house, books have become a “luxury” for Syrians.

Surging printing costs and logistical difficulties linked to power cuts have combined to make books too expensive for most, the 70-year-old told AFP.

“People’s priorities are food and housing,” he said.

‘Lost our readers’

Six years ago, Amer Tanbakji converted his publishing house in Damascus to a stationery store in the hope of attracting new business.

The publishing house, founded in 1954, couldn’t afford to print new editions, while the currency free fall and sanctions on trade with Syria hampered imports.

The switch to stationery failed to turn the business around, and the store is now up for sale seven decades after it opened its doors.

“It would sadden me if it is converted” into something other than a bookstore or publishing house, Tanbakji said.

Syria used to import 800 publications a day before the conflict, but the number has now dropped to just five, said Ziad Ghosn, the former director of the main state-run publishing house.

Printing costs have increased by at least 500 percent over the past two years as transport and labour costs have soared, he said.

Newsstands have been virtually empty since the Covid-19 pandemic prompted authorities to halt the printing of all newspapers in government-held areas last year.

The flagship dailies of the state-run press are now available online only.

Despite mounting difficulties, Samar Haddad said she was not willing to give up.

She moved the Dar Atlas publishing house, founded by her father in 1955, to a basement to cut costs.

From an original staff of 13, Haddad has kept just one employee, who works part-time.

Haddad said she can still print seven books a year, down from 25 before the war.

“We have lost our readers… many have travelled” to escape the war, she told AFP among rows of forgotten novels.

But Haddad vowed she would fight on to keep her father’s legacy alive.

“I will do everything to survive. I won’t close down Dar Atlas.”