With global equity markets like the London Stock Exchange planning to relax norms to get more companies listed, the response from the Middle East corporates has been encouraging.

At the same time, some companies from the region, citing various reasons — one of them being corporate governance — have been pursuing plans to become private by buying back their shares from the global markets.

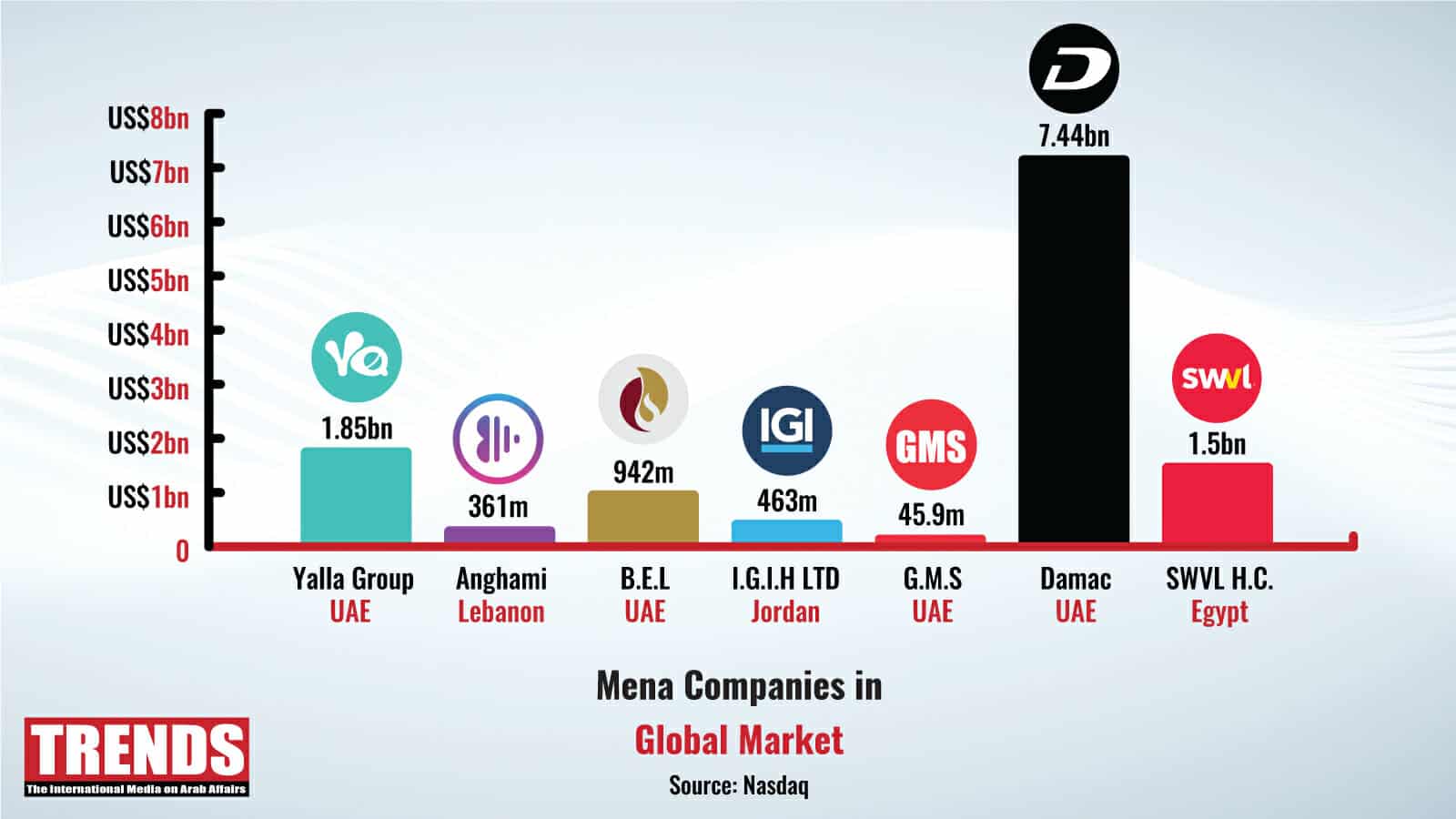

Companies such as Beirut-based Anghami and Egyptian ride-sharing company SWVL were listed on Nasdaq to raise funds and expand their global footprint, while recent listings by Al Noor and NMC Health of UAE and their subsequent inclusion in the FTSE UK series showed the high standards of disclosure and governance in Middle-East companies.

Exit from global markets

However, two prominent Dubai companies — Dubai parks operator DXB Entertainments and Dubai ports operator DP World — have de-listed from the Dubai Financial Market and Nasdaq Dubai since the beginning of 2020.

Damac, the first real-estate company to be listed on Nasdaq in December 2013 and subsequently on the Dubai Financial Market in January 2015, also decided to become private after buying back its shares.

In a statement, Damac said: “With reference to the disclosure published on the Dubai Financial Market’s website dated 9 June 2021 regarding the intention of Maple Invest Co Limited to acquire shares in the share capital of DAMAC Properties, and given that the Securities and Commodities Authority is undergoing a review in this respect, it has been decided to postpone the acquisition procedures until the review is concluded. [sic]”

Dubai real-estate fund Emirates REIT and its fund manager Equitativa (Dubai) said the firm was considering delisting from Nasdaq Dubai as part of a strategic review.

The board would consider all potential options, but a return to operating as a private REIT seemed in the best interests of the fund and its investors, it said in a regulatory filing to Nasdaq Dubai in July 2020.

“Over the past few months, it has become increasingly clear to the board of Emirates REIT that the advantages of remaining publicly listed are heavily outweighed by the disadvantages,” the regulatory filing said.

The fund said the current climate had affected its share price, leading to a large gap between the stock price and its true value.

Last month, the Emirates REIT declared a net asset value of $1.41 per share as of March 31, but its share price closed at just $0.15 in the subsequent days. The company said the crashing of share value had been exacerbated by a cyclical downturn in the UAE real-estate sector and a challenging operating environment.

A delisting from Nasdaq Dubai would allow Equitativa to focus efforts on its long-term strategy to improve returns for investors. It could consider a relisting at a later date, as part of longer-term plans, the company added.

The Nasdaq-listed Yalla Group Limited, which is the leading voice-centric social networking and entertainment platform in the MENA region, also announced a share repurchase program under which the company might repurchase up to $150 million over the next 12 months.

The decision was taken considering the company’s strong cash position, to protect shareholders’ value, and to demonstrate the company’s confidence in its continued growth and long-term prospects, Yalla said in a statement.

Dubai-based NMC Health has requested its shares be delisted from the LSE after they were suspended before the outbreak of the pandemic in 2020.

The suspension followed an application form one of the company’s biggest lenders, Abu Dhabi Commercial Bank. That move followed NMC revising its debt position to $6.6 billion.

LSE may relax norms

The LSE can look forward to more changes following Lord Hill’s review of the UK’s listings rules’ recommended changes to bring the market more in line with the US.

Allowing dual-class share structures on the LSE’s premium segment, giving directors better voting rights, a reduction in the free-float requirements in an IPO, and a review of the prospectus requirements on companies were among Hill’s recommendations to the UK government.

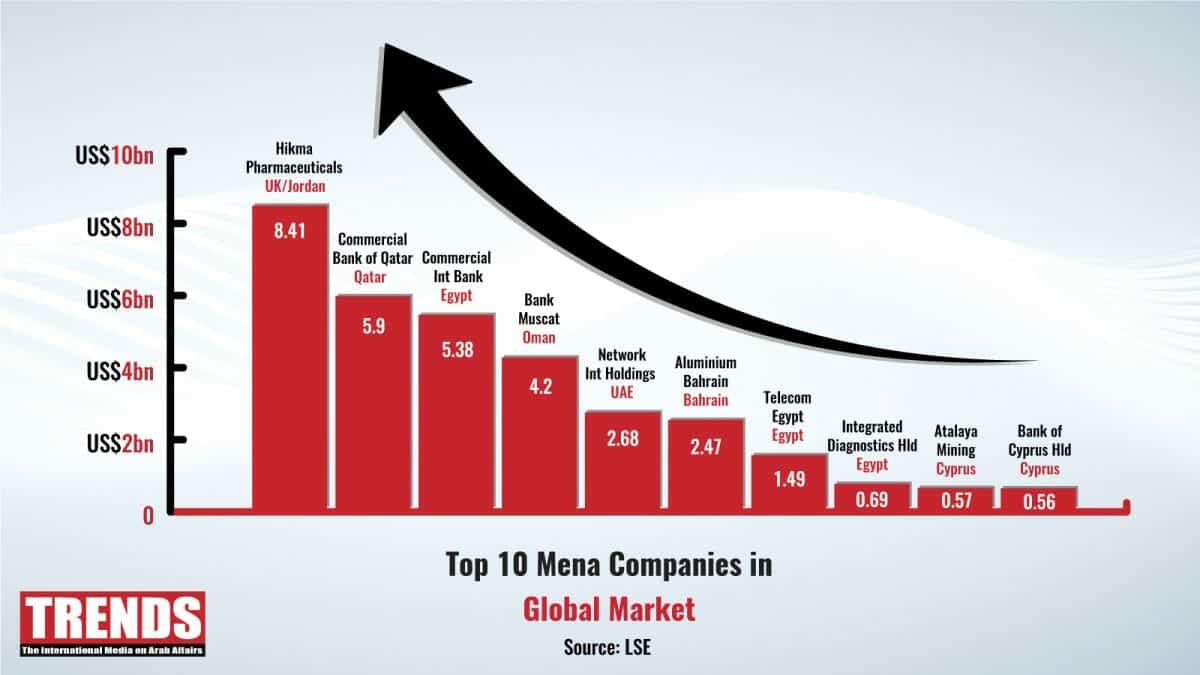

At present, more than 40 companies from the MENA region, including Orascom Telecom (Egypt) and Qatar Commercial Bank and Ooreedoo (both from Qatar) are listed on the LSE.

DP World got itself listed on Nasdaq in 2014, but exited after six years.

One reason cited for the companies wanting to become private again is that they could neither raise expected capital nor follow the transparency norms — like disclosure of accounts, better management practices, and corporate governance — for various reasons.

As most of the companies are family-owned businesses that do not have any obligations to follow the rules prescribed by regulators, these entities have no interest in getting listed on local as well as global markets.

Why Middle-East companies?

After the expiry of the UK’s Brexit transition agreement with the EU earlier this year, nearly $7 billion of daily trading in EU stocks took flight from London to other EU markets.

The resource-rich countries in the Middle East are always happy hunting grounds for global stock markets, and the aforementioned stock flight was one of the reasons the LSE chose to target more listings from the region, as there has been a dearth of initial public offerings following Brexit.

When the first talk of Brexit became public, money raised on the LSE’s equity markets fell nearly 40 percent in 2016 to $32 billion. Despite uncertainty over Brexit on how markets would react, the LSE turned its focus on Middle East.

The global financial crisis wreaked havoc in many countries in 2008, but the Middle East was one of the only regions which remained unscathed. Prior to 2008, LSE courted Russian companies, landing depository receipt listings of Sistema, Megafon, and Gazprom.

Success not guaranteed

Akber Khan, senior director of Asset Management at Al Rayan Investment in Qatar, said some Gulf companies have listed in London but there is no guarantee of success. He explained that adopting a secondary listing adds expense and additional regulatory requirements.

A Gulf company only listed outside the region may gain international investors it might not otherwise, but would lose out on retail interest from its home market; in addition, many Gulf institutions are unable to invest outside the region.

“Companies who believe their businesses or business models aren’t fully appreciated in the Gulf may select an international listing to seek a fuller valuation. However, DP World, one of the world’s largest port operators, ended up delisting from London due to a lack of trading liquidity and investor interest,” explained Khan.

All regional foreign currency debt issuers raise a portion of their capital from international investors.

“As disclosure and transparency improve, companies with listed equity are attracting more actively managed international funds. These investors will demand further enhancements in governance and evidence of improvements in matters relating to the environment and other stake holders,” added Khan.

Brexit enthuses MENA companies

The exit of Britain from the European Union from February 1, 2020, enticed MENA companies, which decided to try their luck by joining the LSE and reap handsome rewards.

Even the LSE too has been considering to relax norms to attract major companies from the region, such as the $1.9-trillion Saudi oil major Aramco, to increase the market capitalization, but no progress has been made so far.

Aramco has plans to raise $100 billion out of an estimated $300 billion in Saudi Arabia’s privatization program by 2022.

The US, Hong Kong, Singapore, Tokyo, and Toronto stock exchanges are also seeking a slice of the Aramco IPO pie, and Saudi officials are in touch with these exchanges to decide where the shares should be traded.

Many companies, while listing on Nasdaq and NYSE, hoped they could easily tap the over-$98-trillion markets with much ease, as the number of shareholders were much higher than the entire population in the MENA region.

But geopolitical events in the last decade, like the US government involved in conflicts in Yemen, Syria, Iraq, Libya, and Somalia, worsened US relations with countries such as North Korea, Iran, China, and Turkey. And then Covid-19 surfaced.

Developments like these prompted companies to think twice before they put their money in US markets.

The US government’s fight with China resulted in three major Chinese firms leaving the American markets. More global companies are likely to quit if the government orders dual-listed companies to allow the American Public Company Accounting Oversight Board or PCAOB to access their audit files.

More than capital

Tariq Qaqish, CEO of the Dubai-based Salt Fund Placement, said there is more to it than meets the eye in the region’s companies’ push to get listed on the international exchanges, and it is not about enough capital alone.

Some founders believe that listing on international markets will give them higher exposure and more liquidity, which will increase the value of their companies. For others, regulations are more lenient and easier to list than markets in the Middle East.

Yet others see their companies as not represented in local markets, which will be hard to compare valuation matrix to, which puts more pressure on their valuation.

Although regional exchanges did upgrade their laws and regulation in an attempt to attract more IPOs, that’s not sufficient for companies’ founders, he said.

“In my opinion, peer valuation is the main factor for founders to list on international platforms,” he explained.

The region’s leading music-streaming platform Anghami, Egypt-based digital payment processing company Fawry, and Dubai-based fintech Network International provide a range of payment solutions and services in the Middle East and Africa with a core focus on merchants and financial institutions.

In Q2 of 2019, Network International became the largest IPO in London at that time.

“For international investors, the valuation matrix is different from regional investors. Majority of regional investors focus mostly on dividends yield, price-earning ratio and basic fundamentals. For international investors, although companies might have negative EBITDA, they give more attention to market share, future cash flow, unique product, and expansion plan,” he explained Qadish.

Damac eyes opportunity

Regarding the delisting of Damac, Qaqish said it was all about a business opportunity where major shareholder Hussain Sajwani (72 percent) had been acquiring shares below their intrinsic value. The stock had been punished due to this deterioration and drop of the UAE real-estate sector.

Overall, the stock dropped from $1.2 per share in 2018 to $.135 per share in March 2020. It was bad news for minority shareholders and the broader market, affecting confidence in the DFM exchange, he said.

Akber Khan said Damac was an interesting example of a listed company in global markets, which in order to successfully repay its outstanding sukuk upended its business model. Capex was slashed and the company has gone ex-growth, effectively being run for debt holders. A public equity listing doesn’t make sense, he added.

LSE performance in H1 of 2021

Meanwhile, the LSE claimed that the level of support provided to the rapidly evolving capital needs of issuers and investors in the global economy was vividly underlined in a strong and active first-half performance in 2021.

According to a spokesperson, London’s markets have connected increasing numbers of businesses with increasing amounts of capital from around the world.

Raising over $36.92 billion in equity capital in Q1 of 2021, LSE has been Europe’s most active exchange by a considerable margin. It raised 55 percent more equity capital than its nearest European rival and is one of the world’s four most active exchanges.

“More than half of the institutional investors in London Stock Exchange-listed are international,” the spokesperson added.

(With inputs from Hadeel Karnib, research from Marielou Abboud, and graphics from Gabi Abu Khalil)