Turkish doctoral student Gulfer Ulas saw the first edition of her favourite Thomas Mann collection published for 33 liras.

She found the second print of the same two-volume set selling months later at her Istanbul book shop for 70 liras (about $6 at the latest exchange rate).

The jump exemplifies the debilitating unpredictability of Turkey’s raging economic crisis on almost all facets of daily life — from shopping to education and culture.

Publishers fear it could also kill off an industry that offers a rare voice of diversity in a country where most media obey President Recep Tayyip Erdogan’s socially conservative government.

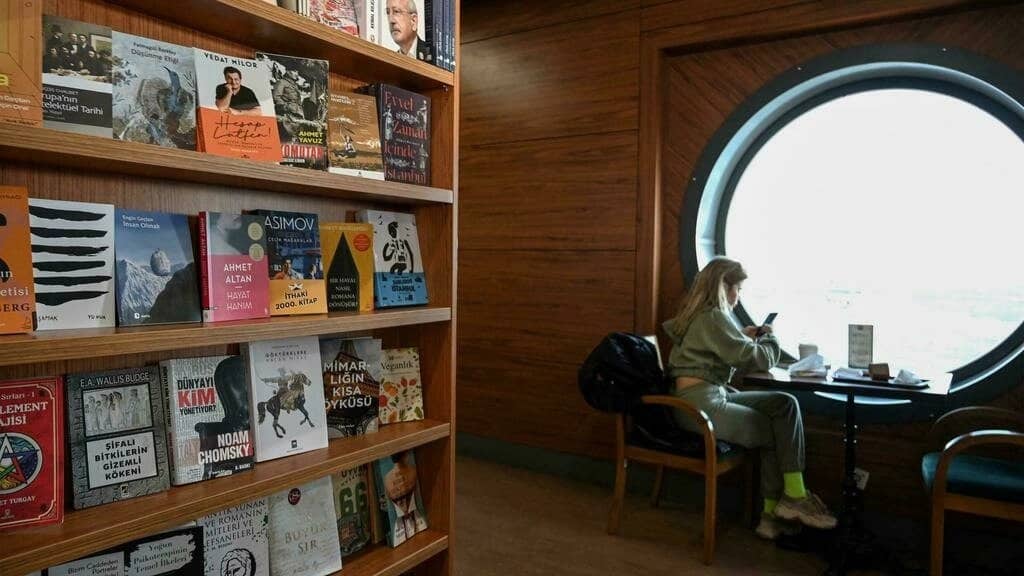

“I am a PhD student in international relations so I have to read a lot. I spend almost 1,000 liras a month on books on my reading list even though I also download from the internet,” Ulas said.

“Book prices are skyrocketing.”

‘Essentials over books’

The Turkish book industry — almost entirely dependent on paper imports – pinpoints one of the flaws in the economic experiment Erdogan has unleashed on his nation of 84 million people in the past few months.

Erdogan has ripped up the economic rule book by orchestrating sharp interest rate cuts in a bid to bring down chronically rising consumer prices.

Economists struggle to remember the last time a big country has done something similar because cheap lending is widely presumed to cause inflation — not cure it.

Turks’ fears about further erosion of their purchasing power prompted a surge in gold and dollar purchases that erased nearly half the lira’s value in a matter of weeks.

The accelerating losses forced Erdogan last week to announce new currency support measures — backed by reportedly heavy exchange rate interventions — that have managed to erase a good chunk of the slide.

Few economists see this as a long-term solution. The lira now routinely gains or loses five percent of its value a day.

Kirmizi Kedi publishing house owner Haluk Hepkon says he fears all this uncertainty “will compel people to prioritise buying essentials and put aside buying books”.

“You publish a book, and let’s say it becomes a hit and it costs 30 liras. And you go to a second edition in a week and the price climbs to 35 liras,” Hepkon told AFP.

“Then for the third or fourth printing, only God knows how much it will cost.”

‘Paying the price’

Turkey’s last official yearly inflation reading in early December stood at 21 percent — a figure opposition parties claim is being underreported by the state.

The next report on January 3 is almost certain to show a big bump because the lira’s implosion has ballooned the price of imported energy and raw materials such as those needed to make paper.

Applied economics professor Steve Hanke of Johns Hopkins University calculates Turkey’s current annual inflation rate at more than 80 percent.

Turkish Publishers Association president Kenan Kocaturk said global supply chain disruptions caused by the coronavirus pandemic have contributed to his industry’s problems by raising the price of unbleached pulp.

Turkey imports the raw material because its own paper mills have been privatised and then largely shut down.

“Only two of them continue production while the others’ machines were sold for scrap and their lands were sold,” Kocaturk said.

“Turkey is paying the price for not seeing paper as a strategic asset.”

‘Resistance’

Publishers are already trying to minimise risks by planning to put fewer books in print in the coming year.

The Heretik publishing house says it will not print some books “due to the rise in the exchange rate and the extraordinary increase in paper costs”.

Aras publishing house editor Rober Koptas said he was worried because printers represented a voice of ideological “resistance” in Turkey.

“Almost the entire press speaks in the same voice and the universities are being silenced,” said Koptas.

“But culture is just as important as food, and maybe more so given there is a need for educated people to address economic woes,” Hepkon of Kirmizi Kedi added.

Avid readers such as Ibrahim Ozcay say the crisis is already keeping them from buying their favourite books for friends.

“I was told that the book I want now costs 38 liras. I had bought it for 24 liras,” said Ozcay.

“They say this is due to the lack of paper on the market, which does not surprise me. Everything in Turkey is imported now,” he fumed.