Istanbul, Turkey – Six months after Bashar al-Assad’s fall, Turkey and Israel are both operating in Syria with starkly opposing agendas, stoking fears of a confrontation unless they find a way to coexist, analysts say.

The reports — officially denied by Israel — sparked alarm over the possible consequences of any confrontation in Syria, where Turkey is looking to expand its military footprint in support of Damascus, and Israel looks to press its aerial advantage to neutralise potential security threats.

‘An accident waiting to happen’

Ties between the two countries were shattered by Israel’s war against Hamas in Gaza.

The upheaval in Syria has seen Ankara emerge as the closest ally of the country’s new rulers, bringing Turkey into much closer proximity with Israel.

Turkey is a key backer of the Islamist-led HTS rebels who toppled Assad in December, but who Israel sees as jihadists.

Ankara’s close ties to Hamas also worry Israel, which has in parallel to the Gaza war carried out air strikes and ground incursions inside Syria to repel government forces from areas near its border.

“Israel wants to ensure Syria will never again have the capacity to be a military threat and what it’s doing is weakening the central government, while Turkey wants a centralised government that has control and sovereignty,” said Soli Ozel, a senior fellow and Turkey specialist at the Paris-based Institut Montaigne.

“And when the goals are so opposite, it almost makes a clash inevitable. It’s like an accident waiting to happen,” he told AFP.

Turkish officials have voiced frustration at Israel’s operations in Syria, including strikes it says were to protect the Druze minority but that Ankara sees as a threat to its interests and regional stability.

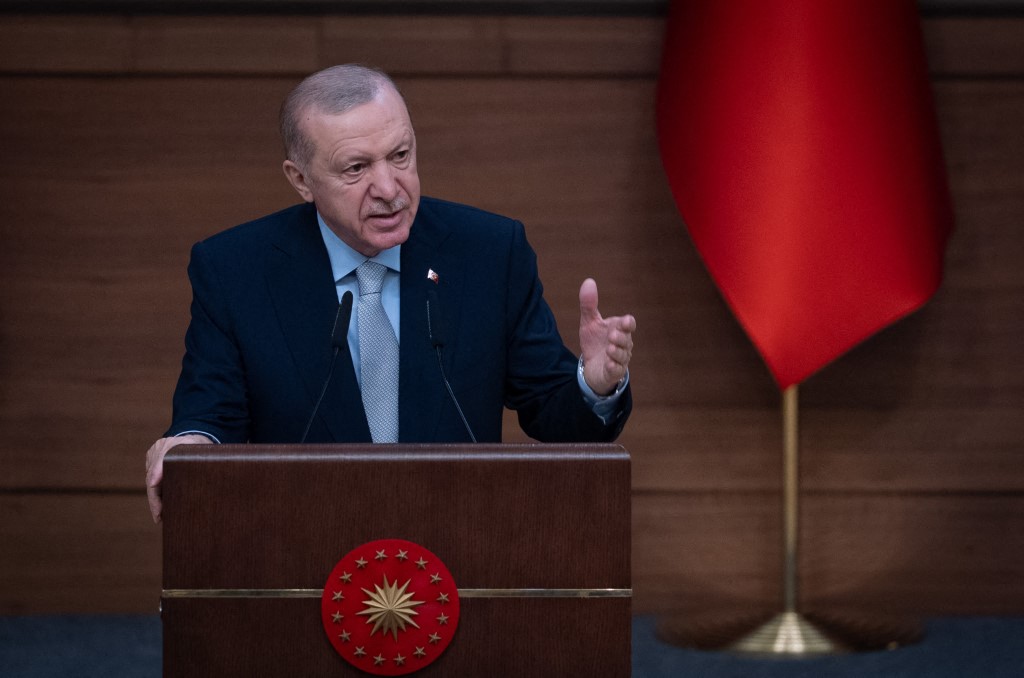

“Israel is trying to dynamite the December 8 revolution by stirring up ethnic and religious affiliations and turning minorities in Syria against the government,” Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdogan said last month.

Diametrically opposed

“Turkey wants a centralised state because decentralisation across its southern borders in Iraq and Syria in the past two decades has not really worked,” said Soner Cagaptay, who leads the Turkish Research Program at the Washington Institute, citing the Islamic State group, the pro-Kurdish PKK and others who have used “the power vacuum to carry out attacks on Turkey”.

Stability was also a prerequisite for the return of nearly three million Syrian refugees still living in Turkey, who have piled domestic pressure on Erdogan.

Israel would prefer Syria to remain weak rather than let Damascus’s Islamist-rooted leaders consolidate their power for fear it could turn into another “Sinwar scenario”, Cagaptay said of the late Hamas leader Yahya Sinwar, who masterminded the October 7, 2023 attacks that sparked the Gaza war.

“Sinwar disguised himself under the rubric of good governance and built an army that attacked Israel and Israelis fear that similar attacks could come from Syria,” he said.

For Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu, an expanded Turkish military presence in Syria under Erdogan — who has accused him of “genocide” in Gaza — is a threat.

“We don’t want to see Syria being used by anyone, including Turkey, as a base for attack in Israel,” Netanyahu said last month.

Israeli warplanes targeted two air bases last month where Turkey was looking to establish military positions, a Syrian source told AFP, in what was widely seen as a warning to Ankara.

Nascent Baku talks

Facing US pressure to resolve their differences, Israel and Turkey held “technical talks” in April in Azerbaijan’s capital Baku.

They have not met since but Netanyahu is expected to meet Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev in coming weeks.

“The trajectory is worrying but it doesn’t mean the sides cannot still put the brakes on,” said Gallia Lindenstrauss, a researcher in Turkish foreign policy at the Institute for National Security Studies.

She noted that during the Syrian civil war, Israel and Russia had a system for avoiding accidental clashes that “worked very well”.

In 2015, Russia and Israel negotiated an understanding in which Israeli fighter jets could carry out strikes in Syria “as long as they didn’t harm Russian personnel or challenge the Assad government or undermine it too severely,” said Aron Lund of the Century International think-tank, suggesting a similar agreement could work between Turkey and Israel.

But Lindenstrauss stressed that the current situation was more complex.

“Turkey is much more ambitious towards Syria than Russia ever was, with grand plans both economically and in terms of energy and security,” she said.