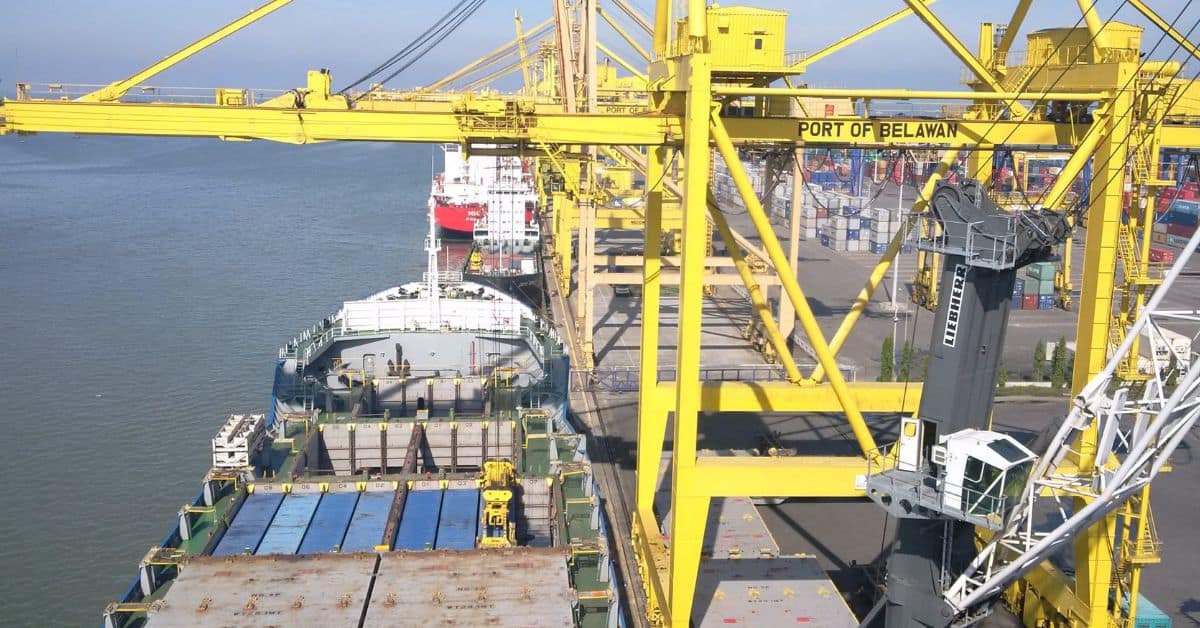

JAKARTA, INDONESIA — There was a report in the media recently that a new shipping connectivity between Belawan port of Indonesia’s North Sumatra province and an Indian destination will be commenced soon. Initiated by the Ministry of State-Owned Enterprises, the reported plan involves Indonesia Port Corporation (Pelindo) and DP World. The tie-up follows last year’s investment commitment from the UAE government worth Rp457 trillion (US$30.187 billion) where the port business is one of the areas of interest.

The Indonesia Investment Authority (INA) will accordingly establish a joint company, perhaps in the form of a capital venture, with the Dubai port operator to handle the new shipping link. This new firm will also invest in the development of the existing container terminal currently controlled by PT Prima Terminal Petikemas (locally known as Prima Petikemas), a subsidiary of PT Pelindo Petikemas, an affiliate of Pelindo.

What is being planned suggests that India-Indonesia maritime connectivity is either flourishing or set to grow exponentially. Is that so? The concern ensues because there are already shipping services connecting the two countries, specifically from the western part of Indonesia. We do not know how these might be affected if the planned new connectivity is established.

The ministry-led program has loopholes that must be pointed out. First, the Belawan-Cochin (DP World has big operations at Cochin in India’s Kerala state) connection plan has no involvement of shipping companies. In many parts of the world, such a service launch would usually be initiated by a container liner while the port operator would facilitate it.

The flaw could be feasibly settled by DP World since as a world-class port operator it has an intensive shipping partner network. But, so far, there is no indication that shipping companies have joined the planned India-Indonesia maritime connectivity effort. It seems the ministry’s plan is out of the blue.

Second, export-oriented container throughput at Prima Petikemas terminal, according to available data, is around 200,000 TEUs per year and the boxes are mostly destined to African countries. There is no information about those shipped to Indian ports. If the new connectivity is established, it will be hard to generate enough cargo for ships serving the route. The hinterland of the terminal, Medan city, and its adjacent regions, are home to massive plantations of rubber and oil palm and their produce is exported mainly in raw form. The suitable transportation mode to ship them out is a bulker or a general cargo vessel, not a boxship.

Significant cargo volume is the critical problem faced not only by the terminal operator but also by other players across the nation except in Java. Here they enjoy a lucrative throughput due to high traffic of manufactured import and export containers. Consequently, terminals in the Jakarta port of Tanjung Priok and Tanjung Perak, Surabaya, East Java, for instance, book aggregately millions of TEUs annually. DP World was a partner of PT Terminal Petikemas Surabaya (TPS) in Tanjung Perak port for several years before quitting it in 2019 after its proposal to continue the partnership was rejected by the then Indonesia Port Corp or Pelindo III.

More container terminals are going to be constructed in Java. Patimban container terminal is set to commence operations in the near future. Besides the upcoming additional capacity, Java has Gresik container terminal, owned by Indonesian conglomerate Maspion Group, in East Java province, and Kendal in Central Java (this one will be funded by Singaporean investment). Oversupply and overcapacity are undoubtedly unavoidable, but the Indonesian government has turned a blind eye to the situation and keeps issuing new terminal and port permits, especially to private entities.

Third, India-Indonesia maritime connectivity is in the state of “do not talk to each other”. Even after 70 years of close bilateral cooperation, there is no major sister port city agreement signed by the two countries’ municipalities. All maritime connectivity is conducted by the third party via Singapore, Hong Kong or other shipping hubs. India and Indonesia simply lack direct maritime connectivity despite abundant import-export cargo.

In this context, what is prepared by the ministry of SOE should be lauded. Nevertheless, they need to look at various other aspects rather than solely focusing on starting a new shipping route. There are several practical measures (geo-economy) to start with. For example, the two states should set up a shipping chamber to promote shipping cooperation as a part of the initiative to establish connectivity in the Indian Ocean. As a business-to-business entity, the chamber could be a sub-unit of the existing trade and industry chamber of the two countries or a separate one. A couple of conferences should be held to allow sector experts to discuss the issues related to increasing shipping connectivity between the two countries.

Additionally, the two countries can order all coal and CPO exports to be transported by Indonesian-flagged vessels and cargo to be packaged to fit containers. For liquid cargo transportation, India and Indonesia can cooperate to procure bigger bulkers to ply the trade. The two counties can also consider appointing transportation attachés at their diplomatic missions to facilitate shipping ventures between Indian and Indonesian companies. To boost its maritime quest, Indonesia may appoint a special envoy or ambassador-at-large to spearhead negotiations with India.

Siswanto Rusdi is the director of the National Maritime Institute (NAMARIN), an independent maritime think tank in Jakarta.

The opinions expressed are those of the author and may not reflect the editorial policy or an official position held by TRENDS.