By Gareth Smyth

On December 18, 2017, a visiting delegation from the International Monetary Fund gave a generally upbeat assessment of the Iranian economy, estimating 4.2 percent GDP growth in the current fiscal year ending in March. Ten days later, protests broke out in Iran’s north-eastern Iranian city of Mashhad, spreading within days to many other cities and centered on people’s anger over price rises, unemployment and corruption.

“It was an explosion,” an Iranian professor told TRENDS. “The people arrested were mainly under 25; many were high-school students. For them, the economy is not the whole story, but it is the most important. All of my family and friends talk about inflation and the lack of jobs.”

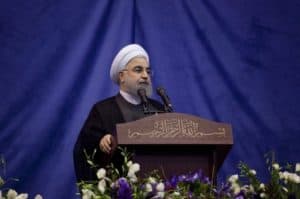

It has been five years since Hassan Rouhani was elected president, when he argued that his predecessor Mahmoud Ahmadinejad had pursued reckless international policies, including the nuclear program that had isolated Iran and sparked international sanctions, damaging the Iranian economy. By 2015, Rouhani reached an agreement with six world powers that saw Iran limit its nuclear program in return for an easing of sanctions. “This gave Iranians an eagerness and optimism that a new era was beginning for them,” said the professor. “But Rouhani is not succeeding with his message of hope. Iranians are starting to think nothing is going to change.”

Scaling up

The IMF believes the Rouhani administration has made progress. Tighter fiscal discipline has brought inflation down from more than 40 percent to approximately 11 percent. Recession in 2013 was transformed into growth largely because a relaxation of United States and European Union sanctions enabled Iran to double its oil and condensate exports to nearly 2.7 million barrels a day. Growth has only just begun to broaden the non-oil sector, says the IMF, which puts non-oil growth for the Iranian year 2016-17 at only 0.8 percent.

Iran’s foreign direct investment (FDI) rose from around $4 billion in 2011 to $11.8 billion in 2017, according to government figures. French oil and gas firm Total reached a $5-billion agreement in July 2017 to lead a consortium to develop phase 11 of the South Pars gas-field, apparently after receiving assurances it would not face US punitive action.

Attracting the interest of the large energy companies is vital for Iran to exploit the world’s largest combined hydrocarbon reserves, 158 billion barrels of oil and 33 trillion cubic meters of gas, both to gain access to advanced technology and to meet a need for investment the government has put at $150-$200 billion. But energy and other would-be investors are cautious. BMI ranks Iran in 12th place out of 18 states in its Operational Risk Index for Middle East and North Africa, citing factors such as “stringent” and “onerous” labor laws, the “pervasive presence of the state in the economy” and “the risk of inter-state conflict”.

The last of these increased in January 2018, when US president Donald Trump suggested the US will withdraw from the 2015 nuclear deal in April and impose new sanctions. These would be in addition to existing US sanctions that are unrelated to the nuclear program. Trump has strengthened those targeted at the Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps (IRGC), whose wide and often opaque business operations foreign investors are concerned to avoid. If the US were to leave the nuclear deal, it is far from clear that Europe, Russia, China and Iran would maintain it.

Facing a downfall

Politics affects Iran’s relations with the Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Iran’s trade with the UAE was strong during the time of sanctions, but is now declining. “In our foreign trade during the first nine months [of the current Iranian calendar year, up to December 21, 2017] the highest fall has been in our trade with the UAE due to several reasons including the political one and also our post-sanction [economic] condition,” Mohammad Lahouti, head of Iran Exports Confederation, said recently. “During sanctions, the UAE played the role of a dealer; many goods were not transported to our ports, they were shipped to the UAE’s ports and from there they came to Iran.”

Sanctions, in other words, gave the UAE a middle-man role it has now lost. Lahouti cited South Korea and Germany as countries now dealing directly with Iran. “We [have] experienced more than 100 percent growth in trade with Europe the sanctions [were lifted]”, he added. Political tensions — with Iran backing Qatar in its stand-off with the GCC — have hardly helped, with allegations that banking services and visas have become more problematic.

Rouhani is struggling to deliver on promises that the nuclear agreement would improve Iranians’ economic situation. In prioritizing fiscal discipline to bring down inflation, his government has left unemployment officially at 12.4 percent, with youth unemployment at 25 percent. Austerity has also led to a fall in the value of the government cash payments, introduced in 2010, on which lower-income Iranians rely. Rouhani’s recent proposal to raise gasoline prices by 50 percent was another major bone of contention in the protests.

The BBC’s Persian service published a study in January, claiming that poverty in Iran had increased by 15 percent in ten years. According to Djavad Salehi-Isfahani, Professor of Economics at Virginia Tech, who has long studied inequality in Iran, the situation is quite a bit more complicated. Utilizing figures from Iran’s Household Expenditure and Income Survey, Salehi-Isfahani finds a “generally low rate of poverty, 4.7 percent for the country as a whole in 2016-17”. But, interestingly, he also finds that Rouhani’s “austerity” policies have led to “increasing poverty rates for urban areas” and “a sharp increase” in rural poverty.

Dilemmas persist

This means the economic improvement under Rouhani has made little if any difference to many outside Tehran. “The economy has continued to grow in the first six months of 2017-18,” writes Salehi-Isfahani, “but we do not yet know if this growth has started to reach down more widely to the poor in smaller urban areas.”

Salehi-Isfahani tells TRENDS he believes Rouhani is on the right course. “I would [advise him to] use the parliament to revise the budget, to combine energy prices increases with higher cash transfers,” he says. “Announcing the 50 percent increase in gasoline while slashing the transfer program [cash handouts] for the lower middle-class was bad politics and bad economics.”

Another serious challenge facing Rouhani was highlighted by IMF representative Catriona Purfield in December: the high level of bad debts left by Ahmadinejad’s populist lending policies. “An asset quality review, related-party lending assessment and a time-bound action plan to recapitalize banks and address non-performing loans should start immediately,” Purfield said, adding that the cost of recapitalizing banks could be covered with long-term government bond issues.

Rouhani also faces political problems. The protests began with the principle-ists, who have long accused the Rouhani government and its supporters of high living.

“The trigger was supporters in Mashhad of Ibrahim Raeisi [who heads the foundation managing Mashhad’s shrine and who stood unsuccessfully in the 2017 general election],” Saeid Golkar, visiting Assistant Professor of Politics at the University of Tennessee at Chattanooga, tells TRENDS. “They forwarded messages, including some with the emblem of the local Basij [the IRGC-linked militia], encouraging people to demonstrate against poverty and high prices. But after a few hours, they lost control and protests appeared in other cities.”

Combating corruption

Iranian politics have long been rife with corruption allegations. December saw the latest round of accusations between Ahmadinejad and the Larijani brothers (including Ali, the parliamentary speaker, and Sadegh, the judiciary chief). This year also saw publication for the first time of the amounts of public money given to leading clerics. “Even religious people have been shocked by all this information,” Golkar tells TRENDS. “For 40 years, there has been talk of the pure values of the Revolution and a public narrative that the clergy are representatives of the hidden Imam [the ninth-century figure who the Shias believe will one day return to introduce social justice]. The gap between expectation and reality is high.”

Another political challenge is reducing the economic sway and political influence of both the IRGC and the religious foundations or Bonyads.“Rouhani’s approach is not necessarily reduction of their power per se but bringing about transparency and accountability,” Farideh Farhi, of the University of Hawaii, tells TRENDS. “This could conceivably lead to a reduction of their power, since many of these organizations are not held accountable because of a lack of transparency.”

It could also mean these bodies paying more in taxes. “To say the least, for budgetary purposes, lack of transparency and accountability means many of the organs engaged in heavy-duty economic activities don’t pay taxes, either because they are given exemptions or it is difficult to track their activities,” says Farhi. “This is why tax revenue as a percentage of GDP is so low in Iran. It has gone up a bit recently, but it is estimated at seven or eight percent of GDP. Such a low percentage may be sustainable for a country with ample fossil fuel revenues and a low population count, but not Iran.”

This is another political challenge. Perhaps after the protests, the political class will tone down its infighting and mud-slinging. But perhaps it will not. Politics in Iran has long been highly factionalized and the government will not have a clear run. “President Rouhani is not the only player in this game, as the Majles [parliament] will take up the issue shortly,” says Farhi. “One likely nod to protests would be not increasing the gasoline prices, or at least not increasing them by 50 percent, as proposed. But some parliamentarians are even talking about bringing back rations and multiple prices, which Rouhani’s economic team is trying very hard to resist.”

The 2021 presidential election, when Rouhani will be ineligible to run for a third consecutive term, is not so far way. Also looming is a more opaque battle to succeed Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, now 78, as supreme leader. Also, the regional struggle with Saudi Arabia shows no sign of abating and the Trump administration has Tehran firmly in its sights. It all adds up to a very uncertain political and business environment.

“There are long-standing problems – Iran’s isolation goes back a long way,” says Golkar. “People are not patient – their hopes for Khatami [Mohammad Khatami, reformist president, 1997-2005] were disappointed; those who had hopes for Ahmadinejad were disappointed. Iranians are starting to think nothing is going to change. These grievances remain. Perhaps there won’t be more protests in the next few months, but they will happen again.”